By Rick Crandall July, 2014 (updated May, 2016)

Uncle Sam means the U.S. and ever since the War of 1812 the personification of the United States as an individual became increasingly popular and eventually iconic. According to historical accounts, Uncle Sam came into use during the War of 1812and was supposedly named for Samuel Wilson, a meat packer who supplied meat to the army during that war.

The first use of Uncle Sam in reference to the United States is not exactly known – one of the earliest uses is asserted in the USS Constitution Museum which discovered a seaman’s journal from March 24, 1810 stating “Uncle Sam, as they call him …” However it is likely that the letters “U.S.” on military supplies (such as wagons, knapsacks and hats) gave rise to the name.

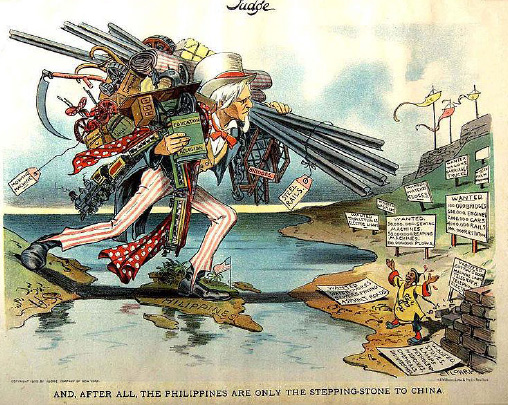

For purposes here, we’re more interested in the visual of Uncle Sam which began appearing in political cartoons, often derisively at first, up through the Civil War, in which he was portrayed in everything from pajamas to eveningwear. He was young, old, fat and thin. At one point he was even a tantrum-throwing toddler. It wasn’t until 1856 that Uncle Sam grew his first beard, which he would alternately gain and lose until Abraham Lincoln was elected President four years later. With Lincoln as President, the Union became associated with the image of a tall, lanky man with a beard — an image that transferred, and stuck, to Uncle Sam forever after as can be seen in the cartoon depictions below from the late 1890’s to early 1900’s.

Fig. 1: 1896 Campaign Button Uncle Sam after the Spanish American War.

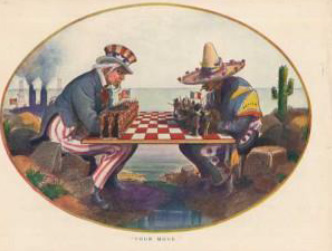

Fig. 2: 1890 cartoon showing Uncle Sam and Mexico playing chess with soldiers.

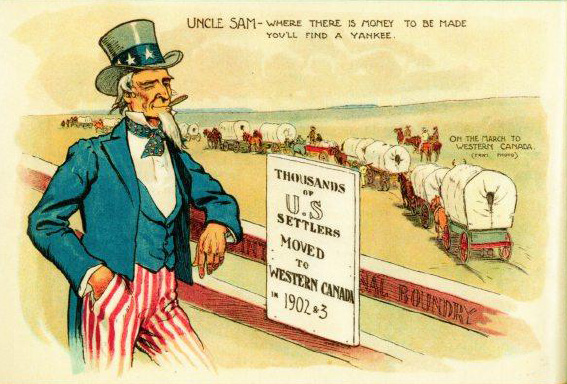

Fig. 3: 1902-03 ad funded by the Canadian Commissioner of Immigration to Saskatchewan in

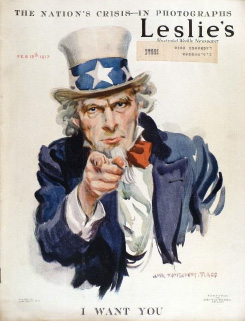

West Farmer magazine promoting the benefits of prairie living.

Fig. 4: 1902 from a Judge Magazine editorial cartoon after US conquest of the Philippines. Uncle Sam stepping across the ocean into the Philippines loaded with symbols of modern civilization.

Fig 5: 1897 cartoon about the U.S.

annexation of Hawaii.

Fig 6: Cartoon celebrating William McKinley’s

2nd Electoral victory over William Jennings Bryan

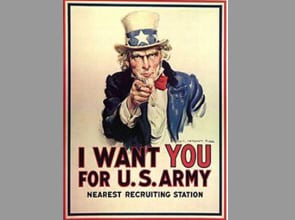

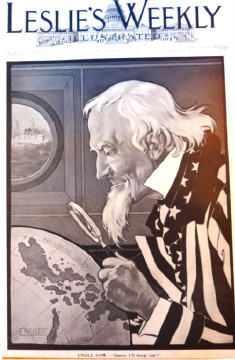

Fig. 7: The poster image of Uncle Sam was shown publicly for the first time in a picture by Flagg on the cover of the magazine Leslie’s Weekly, on July 6, 1916 and again on the cover of the Feb 15, 1917 issue shown above left. More than four million copies of this image were printed between 1917 and 1918. Flagg used his own face for Uncle Sam, and Army veteran Walter Botts provided the pose.

It is said that Uncle Sam didn’t get a standard appearance until the well-known “recruitment” image of Uncle Sam was created by James Montgomery Flagg. Many historical accounts assert that it was this image more than any other that set the appearance of Uncle Sam as the elderly man with white hair and a goatee wearing a white top hat with white stars on a blue band, a blue tail coat and red and white striped trousers.

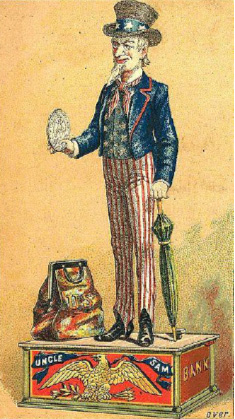

Yet when several early entertainment manufacturers decided to capture Uncle Sam’s image in machine art much earlier than the 1916 Flagg image in Leslie’s Weekly, they were not far off from Flagg’s concept, at least as to the outfit and hair.

Flagg’s image also was used extensively during World War II during which the U.S. was codenamed ‘Samland’ by the German intelligence agency Abwehr. The term was central in the song “The Yankee Doodle Boy”, which in 1942 was featured in the musical Yankee Doodle Dandy.

A Very Early Mechanical Uncle Sam

Mechanical banks began to appear shortly after the end of the American Civil War and the American public was eager to purchase them. This market was generated as a natural outgrowth of the events that occurred during the war years (1862-1865). There was a severe coin shortage during this time, due in part because the public was saving (hoarding) them. In fact, the situation got so bad that postage stamps were often used to make change. Both the Union and Confederate governments began issuing paper notes to supplement their coinage and help relieve this problem. But the public didn’t like paper money. This currency wasn’t trusted. It could become as worthless as last week’s newspaper, especially of the side that would lose the war. However, coins would always retain some metallic value.

Hence, mechanical banks were a product of the times and their popularity remained strong well into the 20th century. Not only were they fun toys with a mechanical animation, but parents could effectively use them to teach their children the practical aspects of being thrifty.

Shepard Hardware Company

One outstanding and important producer of early mechanical banks was the Shepard Hardware Company of Buffalo, New York. Relatively little is known about the Company. Walter J. and Charles G. Shepard were apparently the main principals in the business, which can be surmised by the fact that all Shepard bank design patents were owned or assigned to them. Shepard entered into the mechanical bank field in about 1882 and available information indicates they sold out their line of toy banks in 1892. Shepard produced and sold 15 different banks within a time span of about 10 years.

Uncle Sam Bank

Patent June 8, 1886, # 16,728 description:

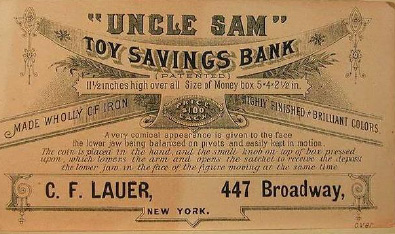

“A comical appearance is given to the face, the lower jaw being balanced on pivots and easily kept in motion. The coin is placed in the hand, and the small knob on top of box pressed upon, which lowers the arm and opens the satchel to receive the deposit, the lower jaw in the face moving at the same time.”

Fig. 8: Original Uncle Sam Bank, with original paint. 11 1/2″ tall. Rick Crandall collection.

Marketing the Uncle Sam Bank

It is a generally accepted fact that Shepard originated the full-color “trading card” method of advertising mechanical banks. These cards are about 2-1/2″ X 5-1/2″ in size and were printed on thick paper stock. They were used by Shepard bank dealers to promote the sale of the banks to their customers. Each card shows the retail price at $1.00 each for a bank. Introductory dealer cards also listed the wholesale bank price, which was $8.50 per dozen. This translates to about 70¢ each, for a 30% wholesale discount. These cards are highly collectible and expensive today.

Fig. 9: An example of a Shepard card for the Uncle Sam Bank.

Penny Arcades and the Uncle Sam Strength Tester

It was a natural for early coin-op machine makers to embody the iconic caricature of Uncle Sam in the form of an entertainment machine designed to attract patronage – especially a coin-operated machine. The ideal locations for coin-op machines were saloons, resort areas and then the onslaught of the “penny arcades” popularized in the very early 1900’s.

Herbert Mills of Chicago’s Mills Novelty Company, once the world’s leading manufacturer of coin operated machines, writes about the Automatic Vaudeville or Penny Arcade business in the early 20th century:

“The Penny Arcade has become a permanent institution as much as the theater, the opera, the circus, the concert, the lecture or the gymnasium, for it combines in a modified form of all of these and because it makes such universal appeal, particularly to the poorer classes, it is destined to grow constantly in popularity and size. Only about 10 per cent of the total population has an income of more than $1,200.00 per year, and therefore, the percentage of those who can afford a dollar for a concert ticket or two dollars for a theater ticket is very small. But everyone can patronize the Penny Vaudeville and afford ten cents for half an hour’s entertainment.”

Lifting Machines, Punching Machines and Grip Testers

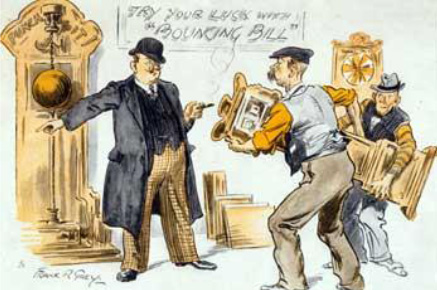

Fig. 10: Proprietor (arranging an amusement arcade):

‘Ere, shove that machine that’s always going wrong next to the punch ball, so that if a bloke loses a penny likely as not he’ll vent ‘is hexasperation in a penn’orth of punch ball.

Athletic test machines were really the first arcade games, but even before that, the first coin-op amusement machines were “exhibition machines.” Examples are Henry Davidson’s Chimney Sweep of 1871 or William T. Smith’s The Locomotive of 1885 (one the first U.S.-made coin-op amusement machine). In the 1880s, various strength testers etc. began to appear in bars and taverns. Actually, they had been there before but in 1885 Robert W. Page of London, England had a coin-op “Hand Shake” machine in the market with a U.S. patent issuance (#373,942) in late 1887. Lifting machines involved pulling on handles; grip testers involved squeezing handles.

By measuring a force applied to a spring or counter-weight, they were in principle similar to weighing scales, although not required to be accurate. They came in many shapes and sizes, and were very popular in the hard living, working class culture of the industrial age. An alternative to arm wrestling, they could be used to settle wagers or impress the opposite sex with demonstrations of physical prowess.

Uncle Sam “Grip Machine” – A Classic

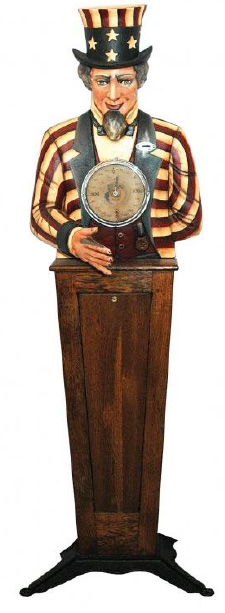

The earliest version of an Uncle Sam grip machine was created by the Howard Company in 1904.

Fig. 11: Howard Uncle Sam at auction in 2006. “66 inches tall, scale and face are all original, some minor paint restoration on upper torso”

Fig. 12: Howard “The Hand Shake” Uncle Sam in original condition

Howard had plenty of Uncle Sam images to choose from in creating its machine. Since there is a stand present instead of a lower torso, a red and white striped jacket with blue lapels were used instead of an all blue jacket – undoubtedly to capture the red, white and blue concept of the full image as shown in the cartoons. The Howard figure shows a more youthful Uncle Sam (darker instead of white hair) and what its flyer called: “a jovial smile on his face” rather than the stern face that would later become the standard after 1916.

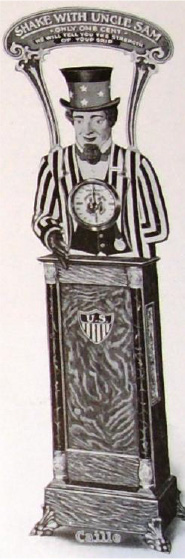

The Caille Uncle Sam

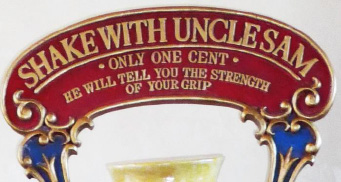

Enter the Caille Brothers Company of Detroit, Michigan, a few years later (sometime between 1906 – 08) with a higher-design version of the Uncle Sam strength tester. Caille was known for seeing a competitive design, cosmetically improving it and releasing its own version. In this case, the Caille version adds a fancy top-sign promoting: “Shake With Uncle Sam; Only One Cent; He Will Tell You the Strength of Your Grip.” The Caille jacket lapels are striped instead of Howard’s blue and the top of the top hat is gray like many of the cartoon images instead of the Howard stripes. Perhaps Caille was avoiding copyright issues or perhaps they were just putting their own ideas on the figure.

There are replicas around. A genuine original is very rare with only 5 or 6 originals being known to exist today. The replicas have either quite different-looking facial castings or have been converted mechanically to be a simple rotating-dial fortune-teller.

Fig. 13: Original Caille Uncle Sam, Rick Crandall collection

Fig. 14: Side view shows the fancy cast cash box cover.

The cast feet have a hole in their tips so that the machine can be anchored to the floor, probably due to the top-heaviness with metal castings on top and wood base – and anticipating users being aggressive with the hand shake to get to 300 and the bell ring!

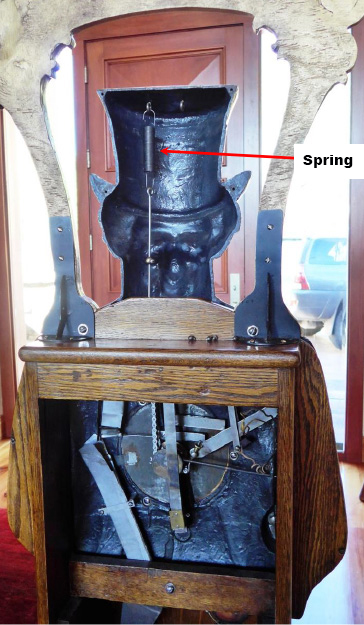

Fig. 15: The interesting mechanism cleverly implements the counter-force for the hand squeeze with a surprisingly small spring indicated by the red arrow. The spring is connected via a vertical rod to a chain wrapped around a sprocket on a shaft that rotates the front dial pointer. To the right of the mechanism you can see the coiled wire connected to a contact that is made when the wheel turns to the 300 mark – which causes the bell to ring from the power of a 1 ½ volt dry cell.

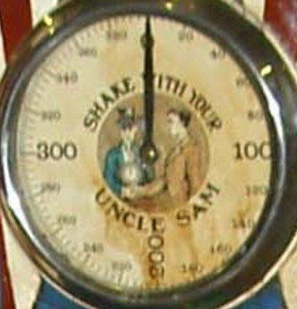

Fig. 16:

Above: lower rear of Sam. On left is the coin chute entering the top of the cash box enclosure. The bell is powered by a 1 ½ volt dry cell battery (on order at the time of this writing). It rings when the hand squeeze is strong enough to register 300 on the front dial.

Right: the cash box fits in the cast enclosure accessed from the side exterior of the machine which is different than many slot machines. Usually the rear door needs to be unlocked to access the cash box, but with the Uncle Sam fastened to the floor through its feet – that would be difficult. The cover plate has the familiar “CB” for Caille Brothers cast into the design. The lock is stamped Caille Bros. on the back. The tag above the cash box enclose says “31” which may be the arcade identification tagging of the machine.

This Uncle Sam was reputed to be originally in service in a Florida arcade. It passed through several hands and was found by Johnny Duckworth for its present home.

Voila! Once in my possession, I disassembled the machine to see how it ticks. After removing the nickel-plated round dial frame and the dial pointers, the good replica of the dial face came off easily and voila! There was the original underneath. There are so few of these in original condition that this kind of evidence of what was there originally is quite important.

Fig 17: Dial face

Caille Catalog Pages:

“In presenting this booklet to you we do so, not only in an effort to sell you machines and novelties, but also in an honest endeavor of placing you in a better financial condition … “

“For so-called closed territories (closed to gambling) we have legitimate machines that are enormous money getters, as for example the weighing or vending types. For open districts we have an endless variety from one slot to eighteen slot designs.”

“The Most Unique of Strength Tests. Shake hands with ‘Uncle Sam.’” Everyone wants to do it, hence this new and novel machine pulls the crowds and brings in the money.”

“The correctly molded cast iron, life-size bust of Uncle Sam is decorated in appropriate shades of red, white and blue enamel and is mounted on a finely built cabinet of selected quartered oak, surrounded by a neat attractive sign. It towers over every other machine and attracts all patriotic Americans.”

“How it works: It’s all in the grip. Is your grip powerful? Prove it by taking a firm grip of Uncle Sam’s hand and making the arrow move around the dial. If it goes to 300 a bell is rung attracting attention to the player and stimulating others to the test. No Penny Arcade or Amusement Park is complete without the Caille “Uncle Sam” Grip Machine and, while it is especially adapted to these places. It is nevertheless a big money maker in every public location.

“Finish: Selected quartered oak cabinet. Nickel trimmings. Handsomely decorated dial with large plain figures. A chased metal ring holds dial glass in position.”

Size 76 x 22 x 12 inches. Weight 115 lbs. Price $50.”

Fig. 18: Caille catalog description of Uncle Sam Strength Tester.

“Descriptions contained herein are partial, but they convey a good idea (i.e. drawings) of the different constructions and their uses…”

Many of the earlier cartoon images of Uncle Sam show him with a blue jacket and red/white striped pants, yet the Howard and Caille machine versions have him with a red/white striped jacket – this idea may have come from the June 9, 1898 cover drawing of Uncle Sam from Leslie’s Weekly showing Sam looking at the Philippine Islands saying “Guess I’ll Keep ‘em.” Here he is shown in the striped jacket and white hair.

Fig 19: Cover of Leslie’s Weekly, June 6, 1898

Fig. 20: This Uncle Sam is a strength tester and appears to be old but of unknown manufacture. It sold at an auction in April, 2006 with the following description:

“A painted cast iron Shake Hands with Uncle Sam Strength Tester, American, early 20th century. The coin operated arcade machine with dial painted red, white and blue, mounted on an iron stand.

CONDITION: Cracked, repaired and repainted.”

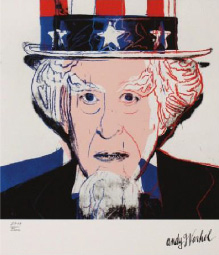

Uncle Sam as Pop Art

Andy Warhol, the renowned painter who created Pop Art, elevated Uncle Sam to that status with his 1981 painting of “Uncle Sam” in his “Myths” portfolio. He often sought inspiration from everyday items (he once called a supermarket a “museum of items”) so I’m not sure where he might have seen an image comparable to his painting as it is quite different from the iconic Flagg poster image.

The closest I could come is from an actual Uncle Sam machine, but it is curious he would have chosen this one, sold from the Charles Fey Museum and Restaurant at a James D. Julia auction on June 28, 2008 calling it:

Fig. 21: Andy Warhol’s 1981 Uncle Sam lithograph, “Myths”

“Caille Brothers Uncle Sam Strength Tester. Perhaps one of the most visually appealing and attractive machines to any collector. An older restoration perhaps done in the 1950s, it is affixed atop a cast iron legged base.”

Fig. 21: Uncle Sam Strength Tester sold from the Marshall Fey collection in 2006 at a James T. Julia auction.

I’m not sure what this really is – the base looks old, the Sam paint job is clearly new and different from the original. Overall it looks nothing like a Caille or a Howard. Perhaps it was a reproduction known to have been done in the 1920’s and again in the 1970’s by The International Mutoscope Company? Regardless, even if the Warhol painting used a repro as a pattern, it surely hasn’t hurt the value of the painting!

Update: About a year after publishing this article, a collector contacted me with the following information about how Andy Warhol developed subjects for his paintings. This clearly indicates that he didn’t copy the machine directly, rather he had a human model dress in a style which is remarkably similar to the machine in Fig. 21. See the human model images in Fig. 22 and text from The Andy Warhol Diaries:

Fig. 22: Left 2 images are from Polaroids of a model actually shot in preparation for the Myths series of prints. Right is a close-up of the Uncle Sam arcade machine from Fig. 21. The Polaroids are from the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts originating from the estate of Andy Warhol and sold by Christie’s at auction.

“January 13, 1981 – I looked for ideas on the New Myths series. Also looked for Mother Goose pictures. But I think the best thing we decided to do is have people come and dress up in the costumes and we’ll take the pictures ourselves, because that way there’s no copyright to worry about.”

(A. Warhol, quoted in P. Hackett, The Andy Warhol Diaries, New York, 1989, p. 354)

Any additional information on an existing Uncle Sam, especially photos would be most appreciated. Send to Rick@AspenVenture.com.